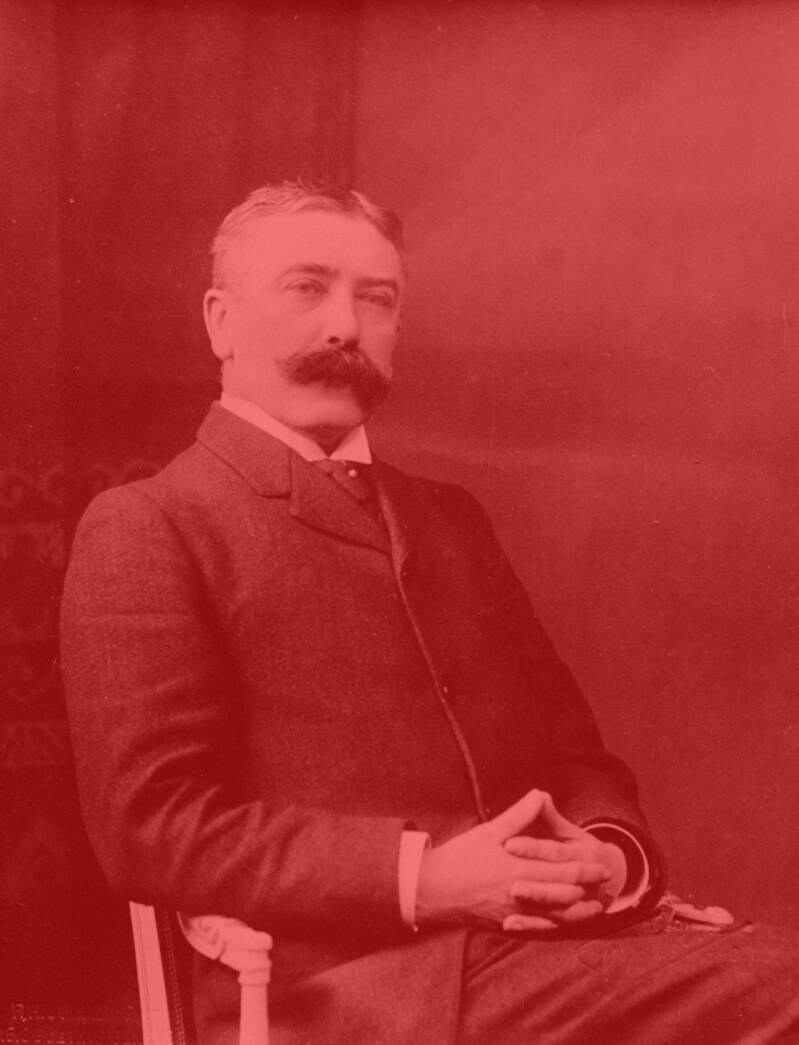

Key theories 1: Saussure

The first major theory of semiology - which later became semiotics - was developed by Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913); a linguist scholar and founding structuralist who developed the basis or groundwork of general linguistic theory. He is well-known for seeing that the theory of linguistic signs should be placed in a more general basis theory, and devised a dyadic formula for the composition of a sign. He defined a sign as being composed of:

- a 'signifier' (signifiant) - the form which the sign takes; and

- the 'signified' (signifié) - the concept it represents.

Saussure held that the sign is the whole that results from the association of the signifier with the signified. The relationship between the signifier and the signified is referred to as 'signification', and this is represented in the diagram below by the arrows.

Saussure elaborates that a sign must have both a signifier and a signified; there cannot exist a totally meaningless signifier or a completely formless signified. A sign is a recognisable combination of a signifier with a particular signified. The same signifier, as in the word 'open', could stand for a different signified (and thus be a different sign) if it were on a button inside a lift ('push to open door'). Similarly, many signifiers could stand for the concept 'open' (like on top of a packing carton) with each unique pairing constituting a different sign.

Nowadays, whilst the basic 'Saussurean' model is commonly adopted, it tends to be a more materialistic model than that which Saussure introduced. The signifier is now commonly interpreted as the material (or physical) form of the sign - it is something which can be seen, heard, touched, smelt or tasted. But for Saussure, the signifier and the signified were purely 'psychological'; he viewed both as form rather than substance:

A later thesis by Saussure goes on to state that the relationship between a sign and the real-world thing it denotes is an arbitrary one. There is not a natural relationship between a word and the object it refers to, nor is there a causal relationship between the inherent properties of the object and the nature of the sign used to denote it. Onomatopoeic words seem possible exceptions, but this is still a construct. For example, there is nothing about the physical quality of paper that requires denotation by the phonological sequence 'paper'. There is, however, what Saussure called 'relative motivation': where a word is only available to acquire a new meaning if it is identifiably different from all the other words in the language and it has no existing meaning.

Structuralism was later based on the idea that it is only within a given system that one can define the distinction between the levels of system and use, or the semantic "value" of a sign. Saussure saw the principle of semiotic arbitrariness as motivated only by social convention. Saussure's theory has been particularly influential in the study of linguistic signs.

As Lévi-Strauss noted, the sign is arbitrary a priori but ceases to be arbitrary a posteriori; after the sign has come into historical existence it cannot be arbitrarily changed. As part of its social use within a code, every sign acquires a history and connotations of its own which are familiar to members of the sign-users' culture. Saussure remarked that although the signifier 'may seem to be freely chosen', from the point of view of the linguistic community, it is 'imposed rather than freely chosen' because 'a language is always an inheritance from the past' which its users have 'no choice but to accept. Indeed, 'it is because the linguistic sign is arbitrary that it knows no other law than that of tradition, and [it is] because it is founded upon tradition that it can be arbitrary'.

The arbitrariness principle does not, of course mean that an individual can arbitrarily choose any signifier for a given signified. The relation between a signifier and its signified is not a matter of individual choice; if it were then communication would become impossible. 'The individual has no power to alter a sign in any respect once it has become established in the linguistic community'. From the point-of-view of individual language-users, language is a 'given' - we don't create the system for ourselves.

Saussure refers to the language system as a non-negotiable 'contract' into which one is born - although he later problematizes the term. The ontological arbitrariness which it involves becomes invisible to us as we learn to accept it as 'natural'.The Saussurean legacy of the arbitrariness of signs leads semioticians to stress that the relationship between the signifier and the signified is conventional - dependent on social and cultural conventions.

Saussure was concerned exclusively with three sorts of systemic relationships: that between a signifier and a signified; those between a sign and all of the other elements of its system; and those between a sign and the elements which surround it within a 'concrete signifying instance'. He emphasised that meaning arises from the differences between signifiers; these differences are of two kinds: syntagmatic (concerning positioning) and paradigmatic (concerning substitution).

The distinction between the set of relationships is a key one in structuralist semiotic analysis. The two dimensions are often presented as 'axes', where the horizontal axis is the syntagmatic and the vertical axis is the paradigmatic. The plane of the syntagm is that of the combination of 'this-and-this-and-this' (as in the sentence, 'the man cried') whilst the plane of the paradigm is that of the selection of 'this-or-this-or-this' (e.g. the replacement of the last word in the same sentence with 'died' or 'sang'). Whilst syntagmatic relations are possibilities of combination, paradigmatic relations are functional contrasts - they involve differentiation. Temporally, syntagmatic relations refer intratextually to other signifiers co-present within the text, whilst paradigmatic relations refer intertextually to signifiers which are absent from the text. The 'value' of a sign is determined by both its paradigmatic and its syntagmatic relations. Syntagms and paradigms provide a structural context within which signs make sense; they are the structural forms through which signs are organized into codes.

Paradigmatic relationships can operate on the level of the signifier, the signified or both. A paradigm is a set of associated signifiers or signifieds which are all members of some defining category, but in which each is significantly different. In natural language there are grammatical paradigms such as verbs or nouns. 'Paradigmatic relations are those which belong to the same set by virtue of a function they share... A sign enters into paradigmatic relations with all the signs which can also occur in the same context but not at the same time'. In a given context, one member of the paradigm set is structurally replaceable with another. 'Signs are in paradigmatic relation when the choice of one excludes the choice of another'. The use of one signifier (e.g. a particular word or a garment) rather than another from the same paradigm set (e.g. respectively, adjectives or hats) shapes the preferred meaning of a text. Paradigmatic relations can thus be seen as 'contrastive'.

A syntagm is an orderly combination of interacting signifiers which forms a meaningful whole within a text - sometimes, following Saussure, called a 'chain'. Such combinations are made within a framework of syntactic rules and conventions (both explicit and inexplicit). In language, a sentence, for instance, is a syntagm of words; so too are paragraphs and chapters. 'There are always larger units, composed of smaller units, with a relation of interdependence holding between both': syntagms can contain other syntagms. A printed advertisement is a syntagm of visual signifiers.

Syntagmatic relations are thus the various ways in which elements within the same text may be related to each other. Syntagms are created by the linking of signifiers from paradigm sets which are chosen on the basis of whether they are conventionally regarded as appropriate or may be required by some rule system (e.g. grammar). Bygone syntagmatic relations highlight the importance of part-whole relationships: Saussure stressed that 'the whole depends on the parts, and the parts depend on the whole'.

To conclude, if it is desirable to convey a particular message to the audience, the author needs to select the right signifiers from the options available in a paradigm of words; it is then the objective to make sure the signifiers are sequenced into a meaningful order, or syntagm.

Whilst Saussure dealt only with the overall code of language, he did of course stress that signs are not meaningful in isolation, but only when they are interpreted in relation to each other. It was another linguistic structuralist, Roman Jakobson, who emphasised that the production and interpretation of texts depends upon the existence of codes or conventions for communication. Since the meaning of a sign depends on the code within which it is situated, codes provide a framework within which signs make sense. Indeed, we cannot grant something the status of a sign if it does not function within a code. Furthermore, if the relationship between a signifier and its signified is relatively arbitrary, then it is clear that interpreting the conventional meaning of signs requires familiarity with appropriate sets of conventions.

Some theorists argue that even our perception of the everyday world around us involves codes. Fredric Jameson declares that 'all perceptual systems are already languages in their own right'. As Derrida would put it, perception is always already representation. 'Perception depends on coding the world into iconic signs that can re-present it within our mind. The force of the apparent identity is enormous, however. We think that it is the world itself we see in our "mind's eye", rather than a coded picture of it'.

According to the Gestalt psychologists - notably Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhlerand Kurt Koffka - there are certain universal features in human visual perception which in semiotic terms can be seen as constituting a perceptual code. We owe the concept of 'figure' and 'ground' in perception to this group of psychologists. Confronted by a visual image, we seem to need to separate a dominant shape (a 'figure' with a definite contour) from what our current concerns relegate to 'background' (or 'ground'). An illustration of this is the famous ambiguous figure devised by the Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin.

The conventions of codes represent a social dimension in semiotics: a code is a set of practices familiar to users of the medium operating within a broad cultural framework. Indeed, as Stuart Hall puts it, 'there is no intelligible discourse without the operation of a code'. Society itself depends on the existence of such signifying systems.

Codes are not simply 'conventions' of communication but rather procedural systems of related conventions which operate in certain domains. Codes organize signs into meaningful systems which correlate signifiers and signifieds. Codes transcend single texts, linking them together in an interpretative framework. Stephen Heath notes that 'while every code is a system, not every system is a code'. He adds that 'a code is distinguished by its coherence, its homogeneity, its systematicity, in the face of the heterogeneity of the message, articulated across several codes'.

Codes are therefore the interpretive frameworks which are used by both producers and interpreters of texts. In creating texts we select and combine signs in relation to the codes with which we are familiar 'in order to limit... the range of possible meanings they are likely to generate when read by other ttrs'. Codes help to simplify phenomena in order to make it easier to communicate experiences. In reading texts, we interpret signs with reference to what seem to be appropriate codes. Usually the appropriate codes are obvious, 'overdetermined' by all sorts of contextual cues. Signs within texts can be seen as embodying cues to the codes which are appropriate for interpreting them. The medium employed clearly influences the choice of codes. Pierre Guiraud notes that 'the frame of a painting or the cover of a book’ highlights the nature of the code; the title of a work of art refers to the code adopted much more often than to the content of the message'. In this sense we routinely 'judge a book by its cover.

Types of code include: -

- Social codes

[In a broader sense all semiotic codes are 'social codes']

- verbal language (phonological, syntactical, lexical, prosodic and paralinguistic subcodes);

- bodily codes (bodily contact, proximity, physical orientation, appearance, facial expression, gaze, head nods, gestures and posture);

- commodity codes (fashions, clothing, cars);

- behavioural codes (protocols, rituals, role-playing, games).

- verbal language (phonological, syntactical, lexical, prosodic and paralinguistic subcodes);

- Textual codes

[Representational codes]

- scientific codes, including mathematics;

- aesthetic codes within the various expressive arts (poetry, drama, painting, sculpture, music, etc.) - including classicism, romanticism, realism;

- genre, rhetorical and stylistic codes: narrative (plot, character, action, dialogue, setting, etc.), exposition, argument and so on;

- mass media codes including photographic, televisual, filmic, radio, newspaper and magazine codes, both technical and conventional (including format).

- Interpretative codes

[There is less agreement about these as semiotic codes]

- perceptual codes: e.g. of visual perception (note that this code does not assume intentional communication);

- ideological codes: More broadly, these include codes for encoding and decoding texts- dominant (or 'hegemonic'), negotiated or oppositional. More specifically, we may list the 'isms', such as individualism, liberalism, feminism, racism, materialism, capitalism, progressivism, conservatism, socialism, objectivism, consumerism and populism; (note, however, that allcodes can be seen as ideological).

These three types of codes correspond broadly to three key kinds of knowledge required by interpreters of a text. These include: -

1. The world (social knowledge)

2. The medium and the genre (textual knowledge)

3. The relationship between 1. and 2. (modality judgements)

The 'tightness' of semiotic codes themselves varies from the rule-bound closure of logical codes (such as computer codes) to the interpretative looseness of poetic codes.

Understanding such codes, their relationships and the contexts in which they are appropriate is part of what it means to be a member of a particular culture. Marcel Danesi has suggested that 'a culture can be defined as a kind of "macro-code", consisting of the numerous codes which a group of individuals habitually use to interpret reality'.

Within a culture, social differentiation is 'over-determined' by a multitude of social codes. We communicate our social identities through the work we do, the way we talk, the clothes we wear, our domestic environments and possessions, and many others ways too. Language use acts as one marker of social identity, but it should be noted that codes are variable not only between different cultures and social groups but also historically.