Existentialism & Structuralism

Basically, existentialism is the philosophical belief that the meaning of everything is a blank, and humans have to by themselves fill in that blank, whether it is for the meaning of the world or that of their own existence; humans have the power and capacity for that task.

Structuralism, meanwhile, believes that whether or not there is meaning to anything, humans would not be able to comprehend it, and that applies to their existence as well; there is no liberty to fill in the blank like suggested by existentialism. Philosopher, Simon Blackburn, said structuralism is: -

"The belief that phenomena of human life are not intelligible except through their interrelations. These relations constitute a structure, and behind local variations in the surface phenomena there are constant laws of abstract structure."

After World War II, France was suffering greatly from the war in the Western World, and needed a champion to help it get back on its feet. Jean-Paul Sartre, the philosopher whose name was one with that of existentialism, became a major figure. The diverse and inconsistent thought currents of the pre-war period that originated from both France and Germany (such as Lefebvre’s Marxism or Nietzsche’s nihilism) was unified by Sartre in one ideology system in his 1943 masterpiece ‘Being and Nothingness’.

Sartre grew great notoriety in both the academic world and the public. His name was so great he outshined almost every other post-war figure. The book ‘Being and Nothingness’ was compared by the philosophy student Gilles Deleuze as ‘a meteor falling on the lecture hall from heaven’; this meaning that the younger generation - no matter how hard they struggled with the limitless creativity they had - could not create anything without passing the influence of Sartre.

Existentialism was the final summit of the development of humanism before the history of Western thoughts changed direction. This, Sartre claimed in his book Existentialism, was a Humanism. It highlighted the absolute stature of human individuality.

Specifically, the core statement of existentialism was “Existence precedes essence”. Put simply, existentialism believed that humans were born without a predesigned fate, whether God or biological-made, whom defined their nature, and the way they would live or die. It held that when a man is born, it is unquestionable that he is existing, but that existence is empty of meaning and nature. This was why Sartre said: “Man is condemned to be free”. It meant that in a life without a predestined fate, humans have to create meanings for their own life, and define what they are. So in order to live a meaningful life, each individual has to realise their emptiness of life purpose and thus set out on a journey to consciously seek for their authentic self. The authentic self is a position within society where the individual finds full consciousness of his own existence, the social responsibility that it bears, as well as of his power to create his own fate and life meaning. Without that, an individual’s existence would, Sartre argued, demonstrate a like of faith.

The legacy still accepted today (the argument) “Existence precedes essence” would be its stand against essentialism and positivism. As existentialism believes that human nature is not predefined, the fact makes it impossible to discover the same by natural science. Instead, a scholar would have to return to a more traditional way to look at humans, namely to see them as constantly changing entities. Sartre believed that humans were constantly in the motion to find their authentic selves and to reach the state of transcendence. This meant that regardless of how an individual was born, his existence could be fixed and intervened with to make him a better individual.

So this is where a lot of people would begin to ask: ‘What purpose does the existence of existentialism serve?’ It didn’t mend a world shattered by the Great War, nor did it contribute any political ground to help with the war that followed it; it did not provide a methodological frame of reference for academic studies, and did not have an answer on what people had to do to make their life better. As a result, existentialism faced lots of criticism, especially since the 50s of the 20th century. Christians would discard it as a rebranded version of atheism. And communists would condemn it as a romantic ideology of the petite bourgeoisie.

There were then the critical theorists greatly influenced by structuralism, who believed that existentialism was trying to pull humans back into some kind of primitive materialism. The senseless universe was one day suddenly occupied by sense-forming humans.

Existentialism has had a significant impact on design. This philosophy's emphasis on freedom, authenticity, and responsibility appeals to many designers. Existentialist designers embrace this concept, producing products and experiences that enable consumers to investigate their own existence and discover their own meaning.

Some existentialist designers focus on designing open-ended goods that allow users to interact with them in a number of ways. This may be seen in the work of designers such as Naoto Fukasawa, who develops items that are simple and quiet but have a lot of room for interpretation.

Individual freedom and the responsibility that comes with it are valued in existentialist philosophy. Fukasawa’s minimalist designs, which are distinguished by their simplicity, are also seen as giving users the ability to interact with objects in their own unique way, free of excessive complication.

Fukusawa’s design language might be difficult to understand for laypeople. However, that is where he applied his existentialist philosophy to design, by enabling others to interpret his work. In fact, this may be considered a piece of artrather than a design.

Other designers create products that force people to consider their own existence. This is seen in the work of designers like Eero Saarinen, who produced furniture that was visually appealing.

Saarinen’s furniture designs, such as the Tulip Chair, were inspired by the human form. They intended to offer comfort and ergonomic assistance. Such designs can compel people to consider the relationship between the designed things they see on a daily basis and their own physical life and well-being.

Existentialist design has its detractors. Some contend that it focuses too much on the individual and overlooks the role of community and social responsibility. Others claim that it is overly negative and provides no solutions to the world’s issues.

Despite these issues, existentialist design is still popular. It is an effective method for developing products and experiences that can help people understand themselves and their place in the world.

Structuralism developed in Europe in the early 20th century - mainly in France and the Russian Empire - in the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure and the subsequent Prague, Moscow, and Copenhagen schools of linguistics. As an intellectual movement, structuralism became the heir to existentialism.

Structuralism and semiotics provide ways of studying human cognition and communication. They examine the way meaning is constructed and used in cultural traditions. Structural semiotics borrowed concepts from structural linguistics to analyze the structure of meaning in non-linguistic systems, from poetics to the traffic code. For example, the formal characteristics of language resemble the rules of chess, the monetary system or the rules of etiquette.

In 1945, Michel Foucault left his hometown, Poitiers, for his education at the famed pedagogical university on Ulm street, Paris — the École Normale Supérieure. Foucault was quick to be identified as a genius, and became friends with Professor Sartre. After a short while, Foucault had grown completely detached from the ideology of the authentic self of humans.

Foucault traveled around Europe and met teachers such as Ludwig Binswanger - the Swiss psychoanalyst who introduced him to the works of the great structuralist Ferdinand de Saussure. And most importantly, Foucault gained access to the works of Nietzsche and came to realize that the free human of existentialism was but an illusion; the reason being that when humans killed God, they had also killed themselves.

The relationship between Michel Foucault and structuralism was complicated; even Foucault himself once said that his ideology was closer to Russian formalism than French structuralism. But, nonetheless, the French press recognised him within the Gang of Four of structuralism, alongside Claude Levi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Lacan.

The progression of structuralism continued to grow in a haywire fashion, and simply cannot be built into a linear timeline as was simpler for existentialism. The reason for this was because structuralism took its roots from many different fields of study such as linguistics, anthropology, and literary criticism.

Contrary to the individual freedom promoted by existentialism, structuralism believes that humans are already aware of their own selves, of the meaning of their lives, of their own birth and death within a structure much greater than themselves. And this structure is often defined by language.

But what does a structure mean in the context of structuralism? While Saussure does not explicitly define it and barely employs the term anywhere in the Course, the two chief concepts concepts, langue and parole (language and speech), are necessary for the understanding of a structure.

According to Saussure, “Language [langue] … is a self-contained whole and a principle of classification.” Here “Language” is used to denote the universal system or structure of grammatical rules and social conventions that is inherent in all languages. In contrast, parole is “the executive side [of Language, that is,] speaking.” Parole is completely controlled by the individual speaker, and it depends entirely on the superseding langue. However, chronologically, one can only begin to understand structures by observing society’s parole: the totality of what is spoken by individuals who use the language. In sum, Language is a structure of signs that precedes and enables the speech acts of individuals. Langue is a structure: parole is an event; the former is abstract: the latter is experiential (real).

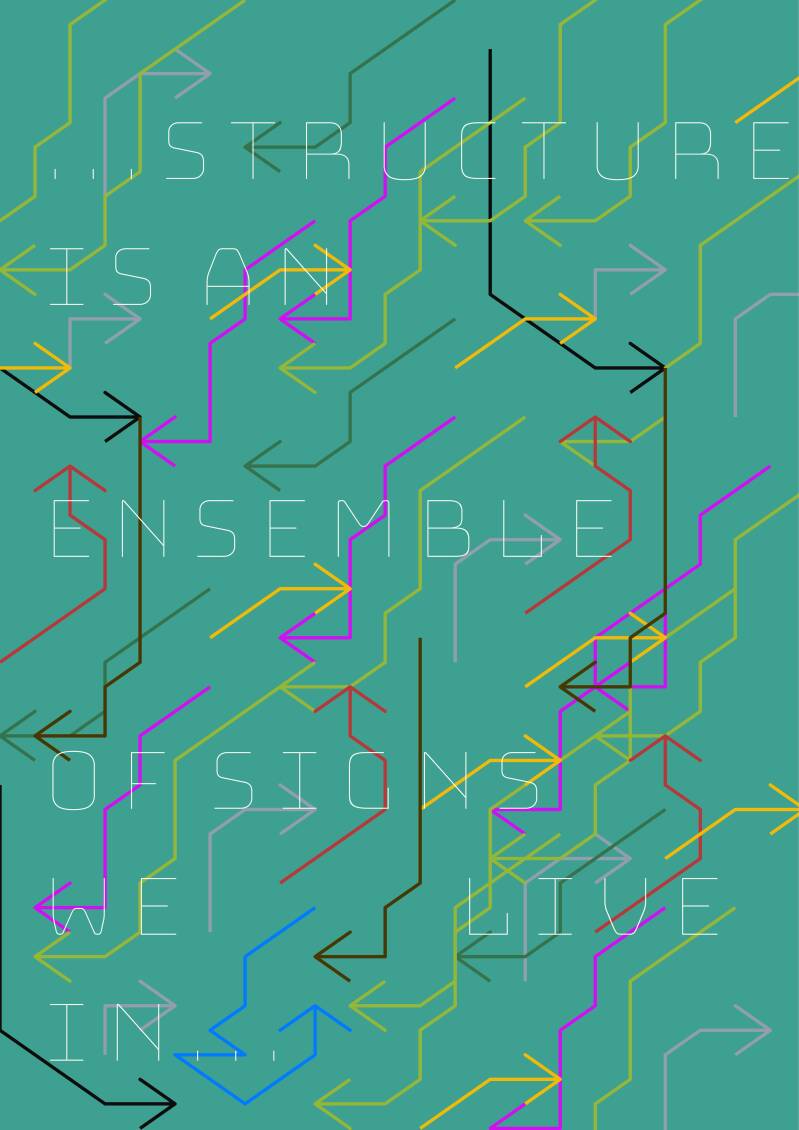

Structure is, then, a system of invisible relations that imposes itself on the visible manifestations (surface phenomena) of reality; an ensemble of signs or quanta that are produced and consumed by the agents, whom enact and recognise their place in the social order through their symbolic practices. Structure is composed of elements that coexist, not elements that are separated chronologically. By means of a structure, a cultural element’s position and value is determined; a cultural element is inescapably bound to its structure — that is the general idea of structuralism. As regards the generalisationof the idea of structure, it is a necessity to transpose it to philosophical discourses. Structure could be the structure of ethics, of knowledge, or of consciousness.

Lois Tyson detects three characteristics of a structure:

- Wholeness, that is, the organic nature of the structure, wherein its properties are emergent. Here, we are reminded of the saying, “The whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

- Transformation, which means that the structure is dynamic. A transformation caused by the structure with its allowed transformational rules could be the syntactical transformation of its “basic components phonemes into new utterances (words and sentences).”

- Self-regulation (analogous to closure property in Group Theory), which means that all transformations of the structure produce results within the structure itself that follows its laws

These ideas originated from the linguist thesis of Ferdinand de Saussure. Saussure believed that all objects and phenomena that we come into contact within our daily life are all signs. To put it simply, humans access and understand the world by putting them into a frame that is a system of signs. A sign has two components — the signifier and the signified.

Saussure made 3 theses on language: -

(1) The vocabulary surface of language is entirely speculative instead of having an absolute origination from the meaning for which it is used to convey;

(2) The signs do not convey meanings by themselves, they only become meaningful when being banded together in a network;

(3) The function of language isn’t to describe the existing world, but instead to help create a different world. Basically, humans exist in the world created by language more than in the physical world.

While arguing that the linguistic world and the physical world were independent of each other, Saussure also had the ambition that the nature of the world could be found within language. Or, precisely, the truth lies at the deepest part of what is being expressed inside our minds.

There were two big successors to de Saussure’s structuralist linguistics, one of whom was the Russian literary critic Roman Jakobson. He was also the coiner of the term “structuralism”. By sheer coincidence, the other successor — the anthropologist Levi-Strauss — also presented in the U.S. around that time, and met Jakobson in a conference. As he returned to France, Levi-Strauss also brought this term with him and developed it into an entire philosophical theory on human science. Levi-Strauss said that the identity of each human and each culture was defined by language structures. There were countless cultures in this world, but the rules of language structure applied universally everywhere. He argued that every culture was built based on the chain of binaries of sign A & what sign A isn’t, such as life-death, love-hate, right-wrong, high-low, clean-dirty, we-other, etc.

Levi-Strauss’s ambition was that by studying the rules existing within language, he would be able to find the nature of humans and culture. He saw that humans have always been the product of the language structure that they belong. Even freedom itself was but a factor that was born within the language and existed under the binary of freedom-slavery. Levi-Strauss named his studies structural anthropology. And this was also the largest nail hammered into the coffin of existentialism.

Structuralists examine how the form of an object relates to its function and underlying purpose. Designers that adopt this outlook ensure that the visual form of their designs aligns with the intended function and message. Each design element serves a purpose and contributes to the overall communication of the design.

Structural semiotics is the study of signs and symbols and their meanings; it explores how signs convey messages and create associations through cultural and social contexts. Designers can leverage structuralist semiotics to create designs that communicate messages effectively. By selecting appropriate symbols, icons, and imagery, designers can tap into cultural and universal meanings to convey messages that resonate with the audience.

Structural analysis is a further application that involves breaking down complex systems or phenomena into their constituent parts to understand their underlying structures and relationships. In design, structural analysis of design elements and layouts can be used to identify patterns, relationships, and hierarchies. Moreover, analyzing the underlying structure of a design can allow designers to identify opportunities for improvement and refinement, ensuring that the design effectively communicates its intended message.

By applying structuralism principles in graphic design, the practitioner can create designs that are not only visually appealing but also meaningful and effective in communicating messages to the audience. Understanding the underlying structures of human perception allows designers to create designs that resonate with viewers on a deeper level, fostering engagement and connection.